By Stefan Pajung & Mihkel Mäesalu

As a historian, it is fascinating to see, how certain subjects attract a lot of attention, are revisited again and again and new interpretations of them are formulated – while other subjects remain unexplained, obscure or only of interest to a small group of individuals. Over the last decade or two, historians from both Denmark and Estonia have revisited the beginnings of mission, conversion and integration of Estonia into the sphere of western Christianity once more, and have come up with a renewed understanding of how the Church established itself in Livonia during the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

On the other hand, far less attention has been paid to how the newly established church institutions and individual clergymen in Livonia interacted with the “motherchurches” in Germany, Denmark and Sweden. While trying to establish how much interaction there was between Denmark and Estonia, we came upon the case of Nicolaus, bishop of Dorpat (Tartu), who in 1313 tried to strike a deal with the bishop of Schleswig, Jens Bocholt, to simply swap dioceses. The bishop of Dorpat proposed to Jens Bocholt that Jens should take over his place in Dorpat, and he, Nicolaus, would then in turn become bishop of Schleswig. But Jens Bocholt wanted none of this – to go to Dorpat and an uncertain future and leave his bishopric behind? He informed Erik Menved, that he had been approached, but declared under oath that he would not go to Dorpat – unless the king approved of it. Why was Jens Bocholt not interested in going to Dorpat and take up residence there? We dug into the sources and tried to find out – and came upon the following story, which actually would touch upon another mystery, namely why Nicolaus of Dorpat was a witness to the newly elected king Christopher II’s coronation charter in 1320.

Seal of the bishop of Dorpat, 14th century

The prince-bishopric of Dorpat as well as the Duchy of Estonia were (almost) neighbors on the edge of western Christendom and faced many of the same problems. While the bishops of Dorpat were mostly on good terms with the Teutonic Order, there always loomed both internal and external threats, which endangered the precarious position of the prince-bishop. The risk of another uprising from the local population was always looming on the horizon and the Russian princes were only waiting for an opportunity to exploit any weaknesses in the defenses of the Livonian territories. This situation led to a natural rapprochement and closer collaboration between Dorpat and the Duchy, who could give each other mutual support in case the Russian princes pounced and intervened in Livonian affairs. It seems likely that the proposed swap in 1313 should be seen in this context – bishop Nicolaus must have felt to be in a precarious position – and not with much cash in hand to improve his situation. We know that Nicolaus went to the papal court in Avignon in early 1313, where he secured a loan of 1500 guilders that was to be used to safeguard the diocese of Dorpat. But he still did not seem to have been content with his situation, as he did not go back to Dorpat from Avignon. Instead, he wrote to the bishop of Schleswig and proposed to swap bishoprics. Subsequently, he was denied by the bishop of Schleswig, but in his reply, Nicolaus must have spotted an opening. He just had to convince the Danish king that the swap would be in his interest.

So, in the spring of 1314, bishop Nicolaus of Dorpat went to Denmark to see if he could persuade Erik Menved (king 1286-1319) and gain his support for the swap with Jens Bocholt. King Erik was willing enough to hear Nicolaus out and gave him right of passage to Denmark so that he might present his arguments. It seems that Erik Menved considered the proposition, but he could not make his mind up, whether the proposition would be such a good idea. In the end, nothing came of it, and bishop Nicolaus had to return to Dorpat none the wiser. Nevertheless, this might suggest that Erik Menved at least considered the option of strengthening his own position in Estonia thorough indirect control over Dorpat. Ultimately, he must have preferred to have a willing “vassal” in Dorpat to collaborate with him instead of having the full obligation and responsibility of having to defend the bishopric of Dorpat as well. Erik Menved was busy enough during these years with his involvement in the conflict with the Hanseatic towns of Rostock, Wismar, Stralsund and Greifswald.

When his plan to leave Dorpat behind and become bishop of Schleswig instead came to nothing, bishop Nicolaus of Dorpat had to think twice about his situation. Even though he was on good terms with the Teutonic Order, alliances in the Medieval world were fleeting. What would happen, if the Russian princes attacked his bishopric? Would the Teutonic Order and/or the Danish king support him then?

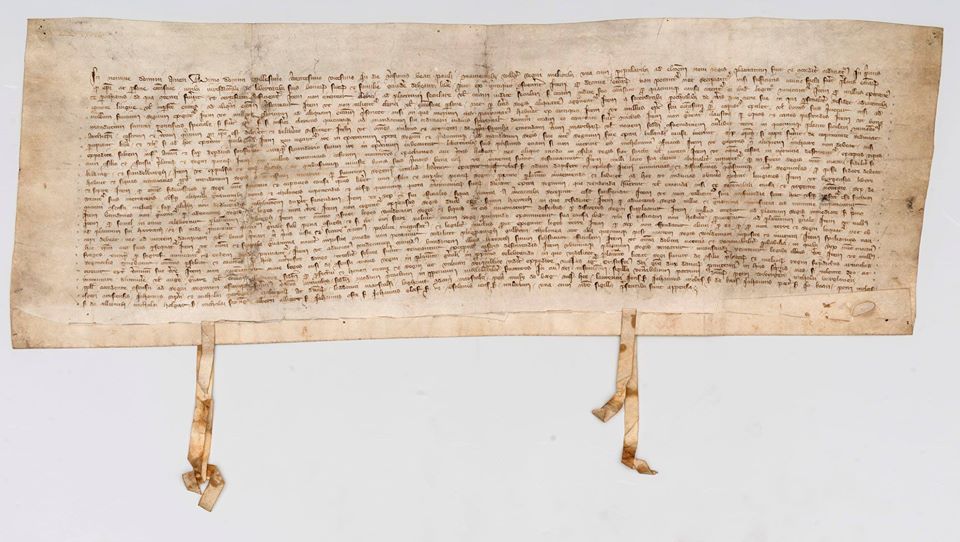

It was better to have additional allies in case the bishopric needed it, and so bishop Nicolaus in the spring of 1319 went first to Lübeck and from there again to Denmark to gather support. Unfortunately, Erik Menved died in November 1319 without a son and heir before any understanding could be reached. King Erik´s brother, Christopher, who from 1303-1307 had been duke of Estonia, was the most likely successor. But in order to become king, Christopher had to sign a rather harsh “håndfæstning”, a coronation charter which severely limited his actions as king and gave extensive concessions to the leading noblemen of the realm. After some negotiations, a text was agreed upon, and on the 25th of January 1320 the agreement was signed by the new king. One of the witnesses was – Nicolaus of Dorpat.

Christopher II’s “håndfæstning” of 1320. Rigsarkivet, Copenhagen

His presence as a witness to Christopher II´s coronation charter has always been a bit of a mystery to Danish scholars, but maybe our research into the church connections between Dorpat and Schleswig has unwittingly brought us closer to an explanation. We do not know, what role Nicolaus played during the negotiations, or if he even had anything to say. But a possible explanation could be that because bishop Heinrich of Reval had died in 1318 at the latest, and no new head of the church in the Duchy had been elected or appointed, Nicolaus de facto came to act as the representative of Danish Estonia. Maybe this was due to the Cistercian Monastery of Falkenau (Kärkna) in the Bishopric of Dorpat held lands in Vironia? Or was it because he was the only representative from Estonia at hand, when Christopher signed his coronation charter in January 1320? Strictly speaking, it was not necessary for a representative from Estonia to be present, as the coronation charter only applied to Denmark itself, but not to Estonia. The reason could be as simple as that he was a credible, independent witness.

We will have to see, if we can come up with a different qualified answer. Maybe another historian can solve the mystery when he or she revisits the subject?