by Stefan Pajung and Mihkel Mäesalu

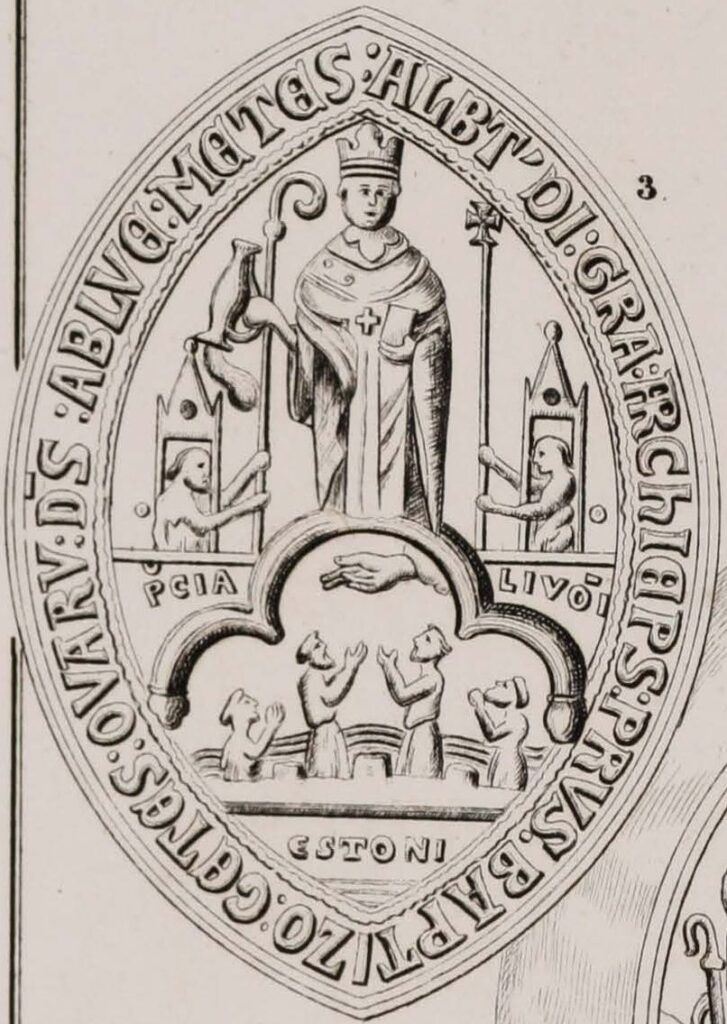

In the winter of 1245-1246, Pope Innocent IV decided to establish a new archbishopric in the Eastern Baltic. This archbishopric of Prussia, Livonia and Estonia was meant for those nine bishoprics – Kulm, Pomesania, Sambia, Warmia, Riga, Semigallia, Curonia, Osilia and Tartu – which did not yet belong to an archbishopric. The first Archbishop of Prussia, Livonia and Estonia was Albert Suerbeer (1246–1273, from 1254 onwards as Archbishop of Riga). As the head of a newly created archbishopric Albert Suerbeer did not have a bishopric of his own – he had to either create one for himself or take over an existing bishopric. This also meant, that he did not have a steady source of income.

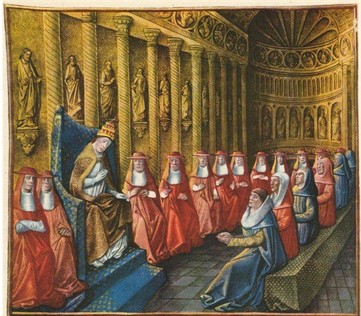

To help Albert Suerbeer in his activities the pope appointed Albert the papal legate to Prussia, Livonia and Estonia, but also to Holstein, Gotland, Rügen and Russia (1246–1250). As papal legate, he was to act as the pope’s direct representative in these regions and was empowered to settle ecclesiastical disputes, which threatened the progress of the Baltic mission. The appointment of a legate was in the Middle Ages not unusual and often used by the papal administration in order to strengthen the link between the pope and the many parts of Christendom, which the pope himself could not visit. Furthermore, the pope appointed Albert administrator – that is provisional bishop – of Lübeck, to provide him with a functioning ecclesiastical office. Albert stayed in Lübeck until the year 1254 and the only part of his legatine area he personally visited was Holstein.

Danish historians have argued that Albert purely was appointed legate to further the missionary activities in the Baltic, making sure that the pilgrim route from Lübeck to Livonia was secure and that the pilgrims could travel safely. At the same time, his assignment turned some heads in Denmark and eventually resulted in a letter of complaint to the pope by archbishop Uffe of Lund (archbishop 1228–1252). What had Albert done to warrant such an annoyed letter from archbishop Uffe?

In 1247, Albert appointed a Franciscan monk named Dietrich as bishop of Virumaa (Vironia) in Estonia. The bishopric of Virumaa had been established by Archbishop Andreas Sunesen of Lund in 1220 and was therefore subject to the Archbishopric of Lund. The bishopric of Virumaa had ceased to exist in the 1220’s when the Order of the Sword-Brothers and the bishops of Riga and Tartu conquered all Danish lands in Estonia. After Valdemar II got northern Estonia back under his rule with the Treaty of Stensby (1238), it was decided that there was no need for two bishoprics in Danish Estonia. King Valdemar II and archbishop Uffe of Lund handed the bishopric of Virumaa over to bishop Thorkill of Tallinn (1240-1260). Unfortunately, they did not officially disband the bishopric of Virumaa, for it was joined with Tallinn only provisionally.

Albert Suerbeer had found out that there had once been a bishopric of Virumaa in Estonia and that at the moment no bishop of Virumaa was in office. Even though the pope had specifically denied Albert’s authority over dioceses belonging to another archbishopric, he still decided to appoint a bishop to this vacant bishopric.

Uffe considered this a serious breach of his rights as archbishop of Lund. The Danish authorities in the Duchy of Estonia must have been quite wary of any interference that could endanger the Danish hold over the Duchy of Estonia, which only quite recently had returned to Danish control and the ecclesiastical authority of Lund, which still needed to find its right footing. Thus, if Albert wanted the collaboration of the local Danish authorities in Estonia with the purpose of promoting the missionary effort in the region, he could not just simply act so rashly by appointing a new bishop of Vironia, but had to be diplomatic and respect the authority of the archbishop of Lund and the bishop of Reval. We do not know exactly what happened next, but Uffe must have written back to Albert and complained about his interference – we don’t know for certain, as this letter has not come down to us. But we know Albert’s reaction to Uffe’s response.

Albert did not want to back down or even apologize to Uffe – instead, he issued a subpoena to the Danish archbishop and wanted him to answer for this affront to his authority. Having received this subpoena, archbishop Uffe then, rather annoyed, wrote to a complaint about Albert to pope Innocent IV, who in November 1248 wrote back to calm Uffe down. It had never been the meaning of the papacy to interfere in Uffe’s authority as metropolitan over Estonia and – this is never said, but rather implied – he should not worry about the subpoena. Had the papacy underestimated the zeal of Albert or how easily the intricate and fragile power relations in Livonia could get out of balance and the region descend into chaos?

We simply do not know. The pope certainly had only a very vague idea of where Estonia was, how large it was and which bishoprics were situated in Estonia, and which in Livonia. This lack of certain knowledge at the papal curia was often misused by cunning bishops and legates – such as Albert Suerbeer – but also by the military religious orders.

At the same time Albert Suerbeer was also in conflict with the Teutonic Order, who refused to let him establish himself in Prussia. By 1249, Albert seems to have stepped on a lot of toes – while not achieving much anywhere, he continued to harass the Teutonic Order as best he could, even handing out penalties to pilgrims who went to Prussia to support the Order’s missionary efforts. Now the papacy had enough – Albert was recalled to Rome, and in September 1250, pope Innocent IV formally revoked Albert’s legatine authority over Holstein, Rügen, Gotland, Prussia, Livonia and Estonia. Additionally, the pope also forbade him to appoint new bishops in Livonia. The following year, the curia’s diplomats succeeded in convincing Albert to come to terms with the Order, who vowed to respect his rights as long as he agreed to abstain from undertaking hostile acts against the Order and promoted its crusading endeavours.

When the bishop of Riga died in 1253, Albert Suerbeer finally had a bishopric large and wealthy enough to suit him as the archbishop. Albert became bishop of Riga in 1254 and from that moment on, the Archbishopric of Prussia, Livonia and Estonia was known as the Archbishopric of Riga.

Albert Suerbeer never abandoned his claim that the Bishopric of Virumaa belongs to his archbishopric. Furthermore, the man he had appointed bishop of Virumaa – Dietrich – held on to this title until the end of his life in c. 1272, even though he spent his whole life in Germany and never visited Estonia. At the same time, the actual bishopric of Virumaa gradually became part of the bishopric of Tallinn. The later remained part of the Danish church province even after the Reformation in Denmark and the disbanding of the Archbishopric of Lund in 1536. The catholic bishopric of Tallinn existed until 1565, when the Swedish authorities, who had taken over Northern Estonia in 1561, appointed a Lutheran bishop for the Swedish province of Estonia.